what did the journalist henry stanley do to help belgium obtain control of congo

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Stanley-1872-631.jpg)

Is willpower a mood that comes and goes? A temperament you're born with (or not)? A skill you learn? In Willpower: Rediscovering the Greatest Human Strength, Florida Country University psychologist Roy F. Baumeister and New York Times journalist John Tierney say willpower is a resources that can be renewed or depleted, protected or wasted. This adaptation from their book views Henry Morton Stanley'due south atomic number 26 decision in the light of social science.

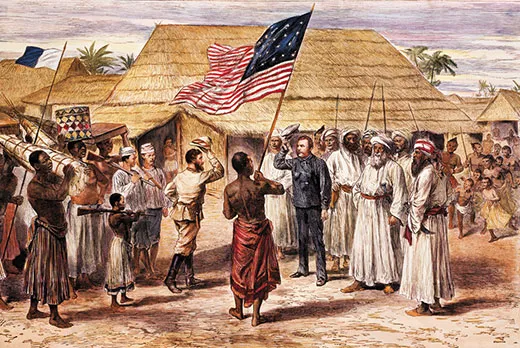

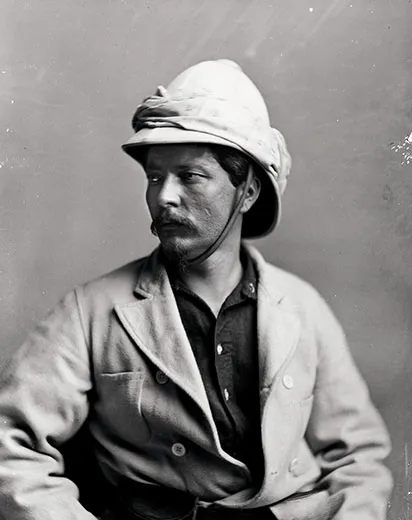

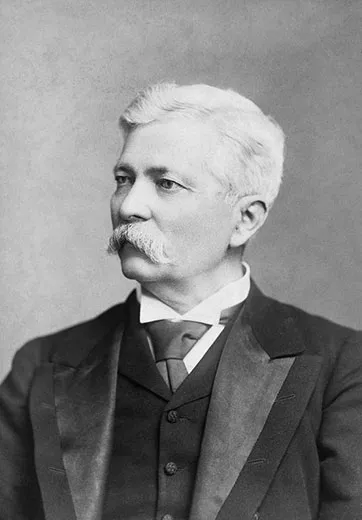

In 1887, Henry Morton Stanley went up the Congo River and inadvertently started a disastrous experiment. This was long afterward his first journeying into Africa, as a journalist for an American newspaper in 1871, when he'd become famous by finding a Scottish missionary and reporting the first words of their encounter: "Dr. Livingstone, I assume?" Now, at age 46, Stanley was leading his third African expedition. As he headed into an uncharted expanse of rain forest, he left part of the expedition behind to await further supplies.

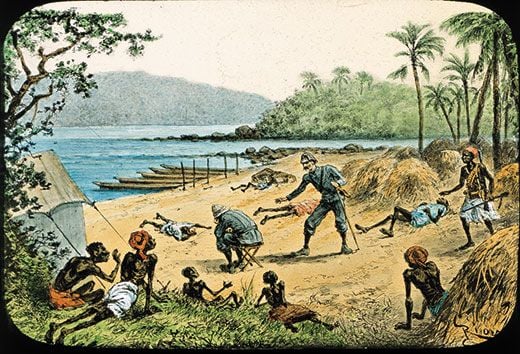

The leaders of this Rear Column, who came from some of the most prominent families in Great britain, proceeded to get an international disgrace. Those men allowed Africans under their control to perish needlessly from illness and poisonous food. They kidnapped and bought young African women. The British commander of the fort savagely beat and maimed Africans, sometimes ordering men to be shot or flogged almost to death for lilliputian offenses.

While the Rear Column was going berserk, Stanley and the forward portion of the expedition spent months struggling to find a way through the dense Ituri rain woods. They suffered through torrential rains. They were weakened past hunger, crippled by festering sores, incapacitated by malaria and dysentery. They were attacked by natives with poisoned arrows and spears. Of those who started with Stanley on this trek into "darkest Africa," every bit he called that sunless surface area of jungle, fewer than one in three emerged with him.

Yet Stanley persevered. His European companions marveled at his "forcefulness of volition." Africans called him Bula Matari, Breaker of Rocks. "For myself," he wrote in an 1890 letter to The Times, "I lay no claim to any exceptional fineness of nature; simply I say, offset life equally a rough, sick-educated, impatient human being, I accept found my schooling in these very African experiences which are now said past some to be in themselves detrimental to European graphic symbol."

In his day, Stanley's feats enthralled the public. Mark Twain predicted, "When I contrast what I take achieved in my measurably brief life with what [Stanley] has achieved in his peradventure briefer ane, the effect is to sweep utterly abroad the ten-story edifice of my ain self-appreciation and leave null backside but the cellar." Anton Chekhov saw Stanley'southward "stubborn invincible striving towards a certain goal, no matter what privations, dangers and temptations for personal happiness," every bit "personifying the highest moral strength."

Simply in the ensuing century, his reputation plummeted as historians criticized his association in the early 1880s with Rex Leopold Two, the profiteering Belgian monarch whose ivory traders would subsequently provide straight inspiration for Joseph Conrad's Centre of Darkness. Every bit colonialism declined and Victorian character-edifice lost favor, Stanley was depicted equally a brutal exploiter, a ruthless imperialist who hacked and shot his way beyond Africa.

But another Stanley has recently emerged, neither a dauntless hero nor a ruthless control freak. This explorer prevailed in the wilderness not because his will was indomitable, but because he appreciated its limitations and used long-term strategies that social scientists are merely now outset to understand.

This new version of Stanley was constitute, appropriately enough, by Livingstone's biographer, Tim Jeal, a British novelist and skilful on Victorian obsessives. Jeal drew on thousands of Stanley's letters and papers unsealed in the by decade to produce a revisionist bout de force, Stanley: The Impossible Life of Africa'due south Greatest Explorer. It depicts a flawed grapheme who seems all the more brave and humane for his ambition and insecurity, virtue and fraud. His self-control in the wilderness becomes even more than remarkable because the secrets he was hiding.

If self-command is partly a hereditary trait—which seems likely—then Stanley began life with the odds confronting him. He was born in Wales to an single xviii-year-quondam adult female who went on to accept four other illegitimate children past at least 2 other men. He never knew his father. His mother abandoned him to her begetter, who cared for him until he died when the boy was 5. Some other family unit took him in briefly, but and so one of the boy'due south new guardians took him to a workhouse. The developed Stanley would never forget how, in the moment his deceitful guardian fled and the door slammed shut, he "experienced for the offset time the awful feeling of utter desolateness."

The boy, then named John Rowlands, would go through life trying to hide the shame of the workhouse and the stigma of his nascence. After leaving the workhouse, at age 15, where he had done cleaning and bookkeeping, and later traveling to New Orleans, he began pretending to be an American. He called himself Henry Morton Stanley and told of taking the name from his adoptive begetter—a fiction, whom he described as a kind, hardworking cotton wool trader in New Orleans. "Moral resistance was a favourite subject with him," Stanley wrote of his fantasy father in his posthumously published autobiography. "He said the exercise of it gave vigour to the will, which required it every bit much equally the muscles. The will required to be strengthened to resist unholy desires and depression passions, and was one of the best allies that conscience could take." At age eleven, at the workhouse in Wales, he was already "experimenting on Will," imposing actress hardships on himself. "I would hope to abstain from wishing for more food, and, to prove how I despised the stomach and its pains, I would divide one meal out of the 3 among my neighbours; half my suet pudding should be given to Ffoulkes, who was affected with greed, and, if e'er I possessed annihilation that excited the envy of some other, I would at one time surrender it."

Years later on, when Stanley first learned of some of the Rear Cavalcade's cruelties and depredations, he noted in his periodical that almost people would erroneously conclude that the men were "originally wicked." People back in civilisation, he realized, couldn't imagine the changes undergone by men "deprived of butcher's meat & bread & wine, books, newspapers, the gild & influence of their friends. Fever seized them, wrecked minds and bodies. Skillful nature was banished past anxiety...until they became but shadows, morally & physically of what they had been in English language lodge."

Stanley was describing what the economist George Loewenstein calls the "hot-cold empathy gap": the disability, during a rational, peaceful moment, to appreciate how we'll carry during a time of great hardship or temptation. Calmly setting rules for how to behave in the future, one often makes unrealistic commitments. "It's really piece of cake to agree to nutrition when you're not hungry," says Loewenstein, a professor at Carnegie Mellon Academy.

It's our contention that the best strategy is not to rely on willpower in all situations. Save it for emergencies. As Stanley discovered, there are mental tricks that enable you to conserve willpower for those moments when it'southward indispensable.

Stanley had first encountered the miseries of the African interior at the age of 30, when the New York Herald sent him in 1871 to detect Livingstone, last heard from some ii years earlier, somewhere on the continent. Stanley spent the first part of the journeying slogging through a swamp and struggling with malaria earlier the expedition narrowly escaped being massacred during a local ceremonious war. After 6 months, so many men had died or deserted that, even afterward acquiring replacements, Stanley was down to 34 men, barely a quarter the size of the original expedition, and a dangerously small number for traveling through the hostile territory ahead. But one evening, during a break between fevers, he wrote a notation to himself by candlelight. "I have taken a solemn, enduring oath, an oath to exist kept while the least hope of life remains in me, not to be tempted to break the resolution I have formed, never to surrender the search, until I find Livingstone alive, or find his dead body...." He went on, "No living man, or living men, shall stop me, just death tin can prevent me. But expiry—not even this; I shall not dice, I will non die, I cannot dice!"

Writing such a annotation to himself was part of a strategy to conserve willpower that psychologists telephone call precommitment. The essence is to lock yourself into a virtuous path. You recognize that yous'll confront terrible temptations and that your willpower volition weaken. So you brand information technology impossible—or disgraceful—to exit the path. Precommitment is what Odysseus and his men used to get past the deadly songs of the Sirens. He had himself lashed to the mast with orders not to be untied no thing how much he pleaded to exist freed to get to the Sirens. His men used a dissimilar form of precommitment by plugging their ears so they couldn't hear the Sirens' songs. They prevented themselves from being tempted at all, which is generally the safer of the 2 approaches. If you want to be sure you don't chance at a casino, you're better off staying out of it.

No one, of course, can anticipate all temptations, particularly today. No thing what you do to avoid physical casinos, yous're never far from virtual ones, not to mention all the other enticements perpetually available on the spider web. Just the engineering science that creates new sins too enables new precommitment strategies. A modern Odysseus can try lashing himself to his browser with software that prevents him from hearing or seeing certain websites. A mod Stanley can employ the spider web in the same way that the explorer used the social media of his day. In Stanley'due south private messages, newspaper dispatches and public declarations, he repeatedly promised to reach his goals and to behave honorably—and he knew, once he became famous, that whatsoever failure would make headlines. As a result of his oaths and his epitome, Jeal said, "Stanley made it impossible in advance to fail through weakness of will."

Today, y'all can precommit yourself to virtue by using social-networking tools that volition expose your sins, like the "Public Humiliation Diet" followed by a writer named Drew Magary. He vowed to weigh himself every mean solar day and reveal the results on Twitter—which he did, and lost lx pounds in v months. Or y'all could sign a "Commitment Contract" with stickK.com, which allows you to pick any goal you lot want—lose weight, stop biting your nails, use fewer fossil fuels, stop calling an ex—along with a penalty that will be imposed automatically if you don't achieve it. You lot can brand the penalty financial by setting up an automatic payment from your credit card to a charity or an "anticharity"—a group you'd hate to back up. The efficacy of such contracts with monitors and penalties has been independently demonstrated by researchers.

Imagine, for a moment, that you are Stanley early 1 morning. You emerge from your tent in the Ituri rain forest. It'southward dark. It has been dark for months. Your stomach, long since ruined by parasites, recurrent diseases and massive doses of quinine and other medicines, is in even worse shape than usual. You and your men have been reduced to eating berries, roots, fungi, grubs, caterpillars, ants and slugs—when you're lucky enough to notice them. Dozens of people were so bedridden—from hunger, disease, injuries and festering sores—that they had to be left behind at a spot in the forest grimly referred to every bit Starvation Camp. You lot've taken the healthier ones alee to expect for food, but they've been dropping dead along the fashion, and at that place's notwithstanding no nutrient to be found. But as of this morn, you're still non expressionless. Now that y'all've arisen, what do you lot do?

For Stanley, this was an easy determination: shave. Every bit his wife, Dorothy Tennant, whom he married in 1890, would later recall: "He had oft told me that, on his various expeditions, he had made it a rule, always to shave advisedly. In the Nifty Wood, in 'Starvation Camp,' on the mornings of boxing, he had never neglected this custom, however great the difficulty."

Why would somebody starving to death insist on shaving? Jeal said, "Stanley always tried to keep a neat appearance—with clothes, too—and fix slap-up store past the clarity of his handwriting, past the condition of his journals and books, and by the organization of his boxes." He added, "The creation of lodge can but have been an antitoxin to the destructive capacities of nature all around him." Stanley himself in one case said, according to his wife, "I always presented as decent an advent as possible, both for self-field of study and for self-respect."

You lot might think the energy spent shaving in the jungle would exist meliorate devoted to looking for food. But Stanley'southward belief in the link between external order and inner self-discipline has been confirmed recently in studies. In i experiment, a grouping of participants answered questions sitting in a dainty cracking laboratory, while others sat in the kind of place that inspires parents to shout, "Clean up your room!" The people in the messy room scored lower self-control, such equally being unwilling to wait a week for a larger sum of money every bit opposed to taking a smaller sum right away. When offered snacks and drinks, people in the keen lab room more often chose apples and milk instead of the candy and sugary colas preferred by their peers in the pigsty.

In a like experiment online, some participants answered questions on a make clean, well-designed website. Others were asked the same questions on a sloppy website with spelling errors and other problems. On the messy site, people were more probable to say that they would risk rather than take a certain thing, expletive and swear, and take an immediate just pocket-size reward rather than a larger but delayed reward. The orderly websites, like the neat lab rooms, provided subtle cues guiding people toward cocky-disciplined decisions and deportment helping others.

Past shaving every day, Stanley could benefit from this same sort of orderly cue without having to expend much mental free energy. Social psychology research would signal out that his routine had some other benefit: It enabled him to conserve willpower.

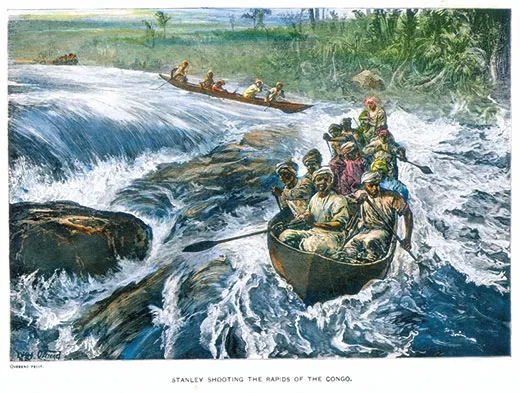

At age 33, not long after finding Livingstone, Stanley constitute dearest. He had always considered himself hopeless with women, but his new celebrity increased his social opportunities when he returned to London, and there he met a visiting American named Alice Superhighway. She was just 17, and he noted in his diary that she was "very ignorant of African geography, & I fright of everything else." Within a month they were engaged. They agreed to ally in one case Stanley returned from his next trek. He ready off from the east coast of Africa carrying her photograph side by side to his middle, while his men lugged the pieces of a 24-foot boat named the Lady Alice, which Stanley used to make the first recorded circumnavigations of the dandy lakes in the heart of Africa. Then, having traveled 3,500 miles, Stanley connected west for the nigh dangerous part of the trip. He planned to travel downward the Lualaba River to wherever information technology led—the Nile (Livingstone's theory), the Niger or the Congo (Stanley's hunch, which would evidence correct). No one knew, because fifty-fifty the fearsome Arab slave traders had been intimidated by tales of bellicose cannibals downstream.

Earlier heading downward that river, Stanley wrote to his fiancée telling her that he weighed just 118 pounds, having lost sixty pounds since seeing her. His ailments included some other bout of malaria, which had him shivering on a day when the temperature hit 138 degrees Fahrenheit in the sun. Just he didn't focus on hardships in the last letter he would acceleration until reaching the other side of Africa. "My love towards you is unchanged, you lot are my dream, my stay, my hope, and my beacon," he wrote to her. "I shall cherish y'all in this light until I run across yous, or expiry meets me."

Stanley clung to that hope for another iii,500 miles, taking the Lady Alice downward the Congo River and resisting attacks from cannibals shouting "Meat! Meat!" Only one-half of his more 220 companions completed the journey to the Atlantic coast, which took nearly 3 years and claimed the life of every European except Stanley. Upon reaching civilization, Stanley got a annotation from his publisher with some awkward news: "I may every bit well tell you lot at in one case that your friend Alice Motorway is married!" Stanley was distraught to hear that she had abandoned him (for the son of a railroad-car manufacturer in Ohio). He was hardly mollified by a annotation from her congratulating him for the expedition while breezily mentioning her marriage and acknowledging that the Lady Alice had "proven a truer friend than the Alice she was named after." But nevertheless badly information technology turned out, Stanley did get something out of the relationship: a distraction from his own wretchedness. He may have fooled himself about her loyalty, simply he was smart during his journey to fixate on a "buoy" far removed from his grim surround.

It was a more elaborate version of the successful strategy used by children in the archetype marshmallow experiment, in which the subjects were typically left in a room with a marshmallow and told they could take two if they waited until the researcher returned. Those who kept looking at the marshmallow quickly depleted their willpower and gave in to the temptation to consume it right away; those who distracted themselves by looking effectually the room (or sometimes just covering their optics) managed to concur out. Similarly, paramedics distract patients from their pain by talking to them about anything except their condition. They recognize the benefits of what Stanley called "cocky-forgetfulness."

For case, he blamed the breakup of the Rear Cavalcade on their leader's decision to stay put in military camp so long, waiting and waiting for additional porters, instead of setting out sooner into the jungle on their ain journeying. "The cure of their misgivings & doubts would have been found in action," he wrote, rather than "enduring deadly monotony." As horrible as it was for Stanley going through the woods with sick, famished and dying men, the journey'southward "endless occupations were too absorbing and interesting to allow room for baser thoughts." Stanley saw the work as a mental escape: "For my protection against despair and madness, I had to resort to self-forgetfulness; to the interest which my job brought. . . . This encouraged me to give myself up to all neighbourly offices, and was morally fortifying."

Talk of "neighbourly offices" may sound self-serving from someone with Stanley's reputation for aloofness and severity. After all, this was the man renowned for perhaps the coldest greeting in history: "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?" Fifty-fifty Victorians found it ridiculous for ii Englishmen coming together in the middle of Africa. Only according to Jeal, Stanley never uttered the famous line. The beginning record of information technology occurs in Stanley's acceleration to the Herald, written well after the meeting. It's not in the diaries of either man. Stanley tore out the crucial page of his diary, cutting off his account merely as they were about to greet each other. Stanley apparently invented the line afterward to make himself sound dignified. It didn't work.

Vastly exaggerating his own severity and the violence of his African expeditions—partly to sound tougher, partly to sell newspapers and books—Stanley ended up with a reputation as the harshest explorer of his historic period, when in fact he was unusually humane toward Africans, fifty-fifty by comparison with the gentle Livingstone, as Jeal demonstrates. Stanley spoke Swahili fluently and established lifelong bonds with African companions. He severely disciplined white officers who mistreated blacks, and he continually restrained his men from violence and other crimes against local villagers. While he did sometimes get in fights when negotiations and gifts failed, the paradigm of Stanley shooting his way across Africa was a myth. The cloak-and-dagger to his success lay not in the battles he described then vividly only in two principles that Stanley himself articulated afterwards his last expedition: "I take learnt by actual stress of imminent danger, in the outset place, that cocky-control is more indispensable than gunpowder, and, in the second place, that persistent self-control under the provocation of African travel is impossible without real, heartfelt sympathy for the natives with whom i has to deal."

Equally Stanley realized, self-control is ultimately about much more than the cocky. Willpower enables united states to get along with others by overriding impulses based on selfish short-term interests. Throughout history, the most mutual fashion to redirect people away from selfish behavior has been through religious teachings and commandments, and these remain an constructive strategy for self-control. But what if, similar Stanley, you're not a believer? After losing his faith in God and faith at an early age (a loss he attributed to the slaughter he witnessed in the American Civil State of war), he faced a question that vexed other Victorians: How can people remain moral without the restraints of faith? Many prominent nonbelievers, like Stanley, responded by paying lip service to religion while also looking for secular ways to inculcate a sense of "duty." During the awful expedition through the Ituri jungle, he exhorted the men by quoting ane of his favorite couplets, from Tennyson's "Ode on the Decease of the Duke of Wellington":

Non once or twice in our fair island-story,

The path of duty was the fashion to glory.

Stanley's men didn't always capeesh his efforts—the Tennyson lines got very onetime for some of them—but his approach embodied an acknowledged principle of self-control: Focus on lofty thoughts.

This strategy was tested at New York Academy past researchers including Kentaro Fujita and Yaacov Trope. They plant that self-control improved amid people who were encouraged to think in high-level terms (Why practice you maintain proficient health?), and got worse among those who thought in lower-level terms (How do you maintain expert health?). Afterwards engaging high-level thinking, people were more likely to pass upwards a quick advantage for something meliorate in the time to come. When asked to squeeze a handgrip—a mensurate of physical endurance—they could hold on longer. The results showed that a narrow, physical, here-and-now focus works against self-control, whereas a broad, abstract, long-term focus supports it. That's ane reason religious people score relatively high in measures of self-command, and nonreligious people like Stanley can benefit past other kinds of transcendent thoughts and indelible ideals.

Stanley, who always combined his ambitions for personal glory with a want to be "proficient," found his calling forth with Livingstone when he saw firsthand the devastation wrought by the expanding network of Arab and East African slave traders. From then on, he considered information technology a mission to end the slave merchandise.

What sustained Stanley through the jungle, and through the rejections from his family and his fiancée and the British establishment, was his stated belief that he was engaged in a "sacred task." By modern standards, he tin seem bombastic. Simply he was sincere. "I was non sent into the globe to exist happy," he wrote. "I was sent for a special piece of work." During his descent of the Congo River, when he was despondent over the drowning of ii close companions, when he was shut to starving himself, he consoled himself with the loftiest thought he could summon: "This poor body of mine has suffered terribly . . . it has been degraded, pained, exhausted & sickened, and has well nigh sunk under the task imposed on information technology; only this was but a modest portion of myself. For my real self lay darkly encased, & was ever too haughty & soaring for such miserable environments as the trunk that burdened it daily."

Was Stanley, in his moment of despair, succumbing to faith and imagining himself with a soul? Maybe. Merely given his lifelong struggles, given all his stratagems to conserve his powers in the wilderness, it seems likely that he had something more secular in mind. His "real self," as the Breaker of Rocks saw information technology, was his will.

Adapted from Willpower, by Roy F. Baumeister and John Tierney. Published by organisation with the Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Group USA. © Roy F. Baumeister and John Tierney.

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/henry-morton-stanleys-unbreakable-will-99405/

0 Response to "what did the journalist henry stanley do to help belgium obtain control of congo"

Post a Comment